Information from Yale Non-Clinical Counselor

Krista Dobson

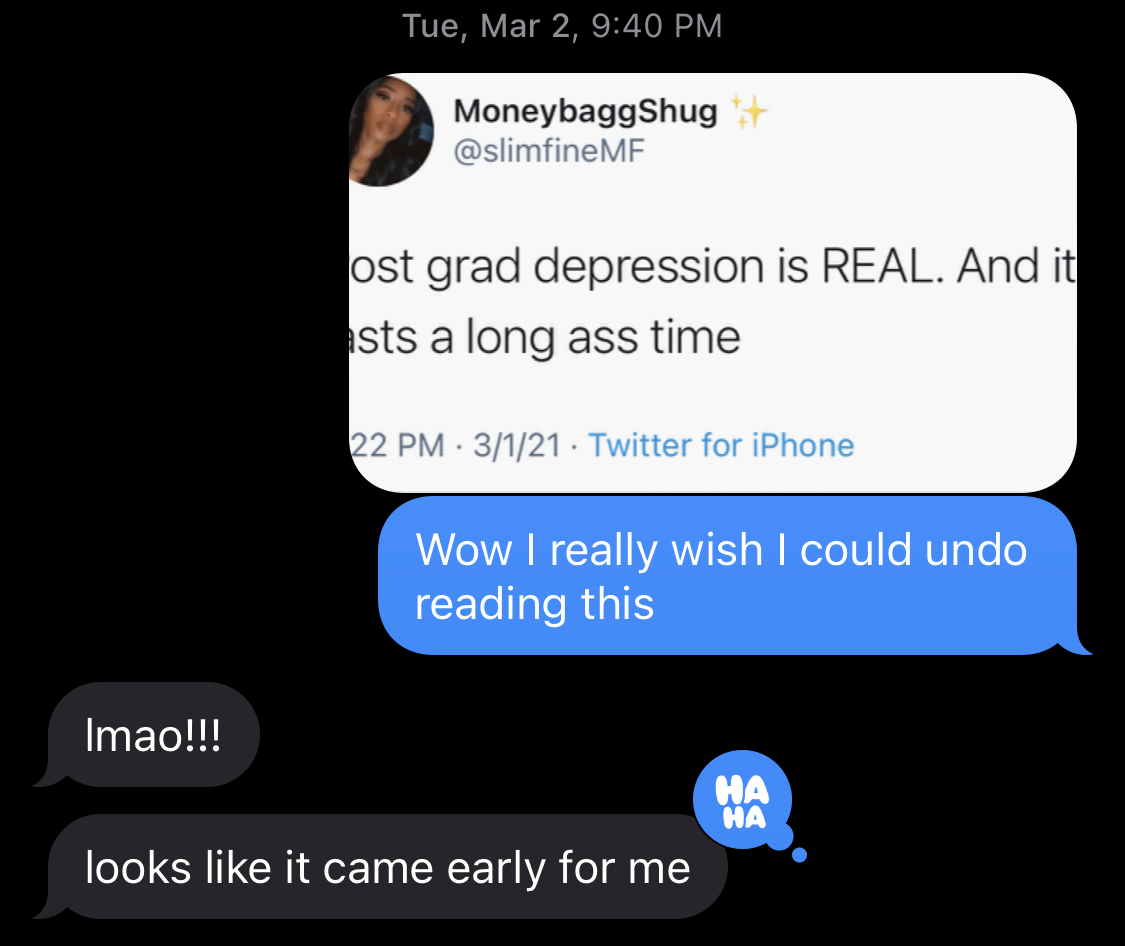

When everything went onlineI was a working in New Jersey as a Counselor at a small, private liberal arts college. Many of the students I supported came from under resourced communities. Housing, unemployment, food insecurity, and lack of access to health and social needs were ever-present concerns often resulting in increased symptoms of depression and anxiety. When social distancing mandates were implemented due to COVID-19, those symptoms were exacerbated. Mental health services transitioned to an online format requiring certification in telehealth. The use of technology as a format to conduct a therapy session was new to me. In the beginning, I found it difficult and grieved the loss of face-to-face sessions. I could see the toll isolation was taking on my students. We discussed how difficult it was to secure laptops, how to navigate unreliable Wi-Fi connections, and how they felt that their education may be compromised by an unprecedented and unexpected shift to online learning. Then sessions focused on the killing of George Floyd and the subsequent protests against continued instances of police brutality. We spoke about the stress and trauma of being a person of color and how that impacts mental health. We discussed how news cycles and social media were a source of information andconnection however also fueled feelings of uncertainly, loss of control, and at times hopelessness. I wasn’t divorced from what my students were feeling as I felt it too. The rhythms of my day consisted of balancing the most intense and demanding sessionsof my entire career, looking at non-stop media coverage, and checking in on loved ones all online and all in isolation. I began feeling directionless and unmotivated. I often discuss with my students that purpose is driven by knowing who you are and what you value. It’s living with intention. I know I value kindness, health, and peace. I began to intentionally limit my time online and curating my social media influences and news feeds that closely reflected my values. I moved more and created more meaningful connections to family and friends even if we couldn’t physically be together. When I was tired I stopped and when I had more energy I did more. I created a sense of peace and control.

For students who are feeling overwhelmed or are looking to “stay sane” in a digital world it is important to prioritize yourself and your well-being.

- Taking time to explore your values and then putting those values into action provides stability and direction when life feels uncertain.

- Maintain a regular routine to enhance stability.

- Take an inventory of how you feel when online especially over a number of hours. Notice if you are feeling increasingly anxious or tired. Then be intentional with the time you are online and limit usage, if necessary.

- Develop a wellness practice such as meditation, yoga, or tai chi to help focus the mind and calm the body.

- When preparing to go online take a moment to ground your attention by taking a few deep breaths, gentle stretches, or utilizing affirmations.

- Stay active, make good nutrition a priority, and try to sleep well.

- Talk to someone. If you are experiencing continued burnout and stress, the following resources are available:

Yale Mental Health and Counseling: (203)432-0290 Mon–Fri 8:30am–5pm.

Afterhours call Acute Care at (203)432-0123 and ask to speak with the

on-call clinician.

Yale Chaplain's Office:

Chat with a Chaplain

Non-Clinical Counselor Krista Dobson:

Schedule a meeting

Scrolling Through Flattened Architecture

Ernesto Ibanez and Pablo Castillo

Last year, around mid-October, So Icy Gang Vol. 1 was dropped, the mixtape number 78 of the Atlanta-based rapper Gucci Mane. Throughout his career, the author of Chicken Talk or Trap-Tacular has generated around 4000 hours of music, has published about 99 singles, and only in 2020, he published three mixtapes. However, he has barely released more than ten studio albums during his career. These figures might have seemed nonsense just a decade ago, but they exemplify both the consumption model and the production strategies that have been established worldwide after the explosion of the digital age. The rhythm of the new audiovisual industry, streaming-based, with free access and immediate consumption, cannot be understood without the way of conceiving music -and its distribution- that arose in Atlanta between 2010 and 2015.

Digitally generated content continues to grow exponentially. Not only is media becoming more accessible, but also the necessary tools for generating this content are constantly growing. In contrast to last century, the current cultural production rate is frenetic. Around 500,000 tweets are generated every minute (!). Approximately 50,000 photos and 277,000 stories are published on Instagram, 400 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube, and around 188,000,000 emails are sent, 85% of which is spam. Every minute. To get an idea, only on YouTube, we generate 65 years of video every day.

The amount of content we generate is now more abundant than ever, and it has two common denominators: on the one hand, it is increasingly encapsulated and, on the other, it is generated from infinite sources -creators- simultaneously. The trend towards fragmentation is clear, and that makes us spend hours generating and, at the same time, consuming content. We produce and consume endless stories and tweets; then, we forget them and move on. The barrier between creator and consumer has almost disappeared.

Capsules.

We observe a global trend towards an ‘encapsulated’ content, created to be consumed in small doses, although, paradoxically, this leads to increasing overall consumption. As noted before, in music, the pattern was releasing full-length albums every two years, but this new way of content-production has led to a reckless pace of music videos and singles just months or even weeks apart. Also, we shifted from books or reports to reading posts on different blogs, but this only lasted shortly because tweets arrived immediately. Even videos started lasting too long when Snapchat and Instagram stories appeared. This trend seems to work as long as the content is generated in dynamic ways, with the intention to impact rather than endure. This is only sustainable—or not even—when we talk about virtual content. However, fashion, technology, or even interior design try to join this frenetic production rate, creating increasingly compressed trends based on launching self-obsolescent products, only leading to ecological collapse. Even so, the trend continues to rise.

When dealing with architecture, the problem is twofold. Not only would the cost of accelerating its obsolescence be very high, but the rhythm of production would not match the one of consumption. Then, should architecture base its relevance on a deliberate act of immediacy? Within this context, what can architecture do for not being forgotten within thirty seconds?

Flattened architecture.

According to Victor Hugo, the speed of book printing jeopardized the purpose of the gothic cathedral, and Scott Brown unveiled that the car speed turned architecture into a symbol in favor of visual communication. Likewise, the accelerated pace of digital media production flattened the architectural space, turning it into a 2D image, a background image whose principal value is purely symbolic and aesthetic, at the service of audiovisual and technologic disciplines.

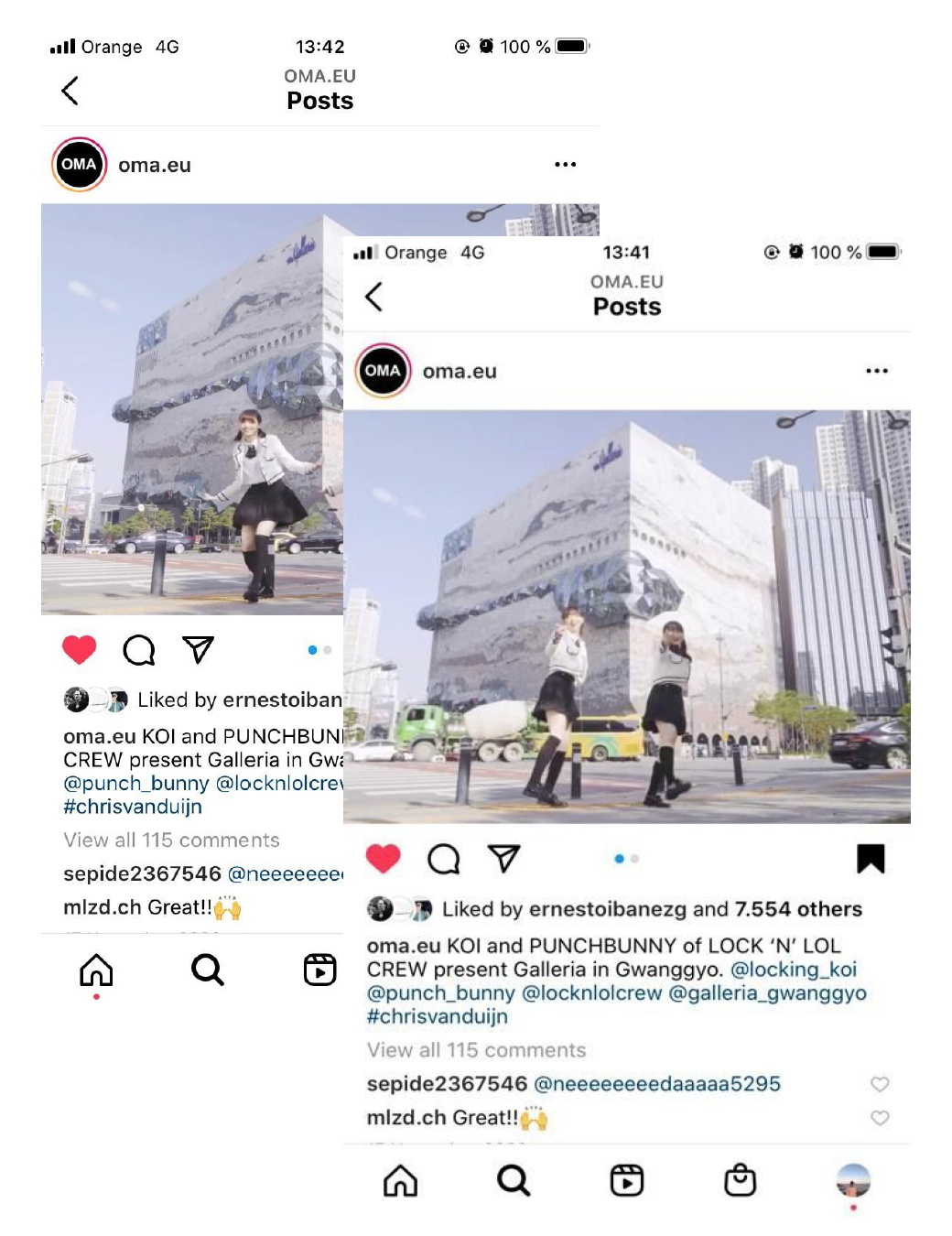

In one of its latest Instagram posts, OMA presented its Galleria in Gwanggyo —one of its recently completed buildings in South-Korea— as a backdrop for a dancing performance by KOI and Punch Bunny, of Lock ‘N’ Lol Crew. In recent years, dance and music videos have adopted modern architecture and the built environment as part of their own discourse.

Space and time are intrinsically linked to the very notion of architecture. However, most of the architectural content we consume has nothing to do with those concepts anymore. Today, time is immediate, and space is flat. As in a futurist painting, the mental overlapping of infinite architectural images in the form of Instagram posts or TikTok backdrops generate an alternative spatiality. The mental image caused by the proliferation and reproduction of digital images substitutes space and time. Scrolling down the screen, we can see the Galleria in Gwanggyo from endless angles, perspectives and at different times of the day. The whole architectural experience has undergone a remediation process. It is not a direct interpretation of the building and its space anymore, but the consumption of its infinite mediated representations. Encapsulated in easily digestible content, Youtube videos and Instagram stories have reproduced its image further than any architectural magazine could ever have. Consequently, architecture has accepted its resignification as the only alternative for keeping up with the accelerated rate of the actual production of content.

iPhone Needs to Cool Down

Lilly Agutu

Evolution Process of Ideas Observed in the Age of COVID

Taku Samejima

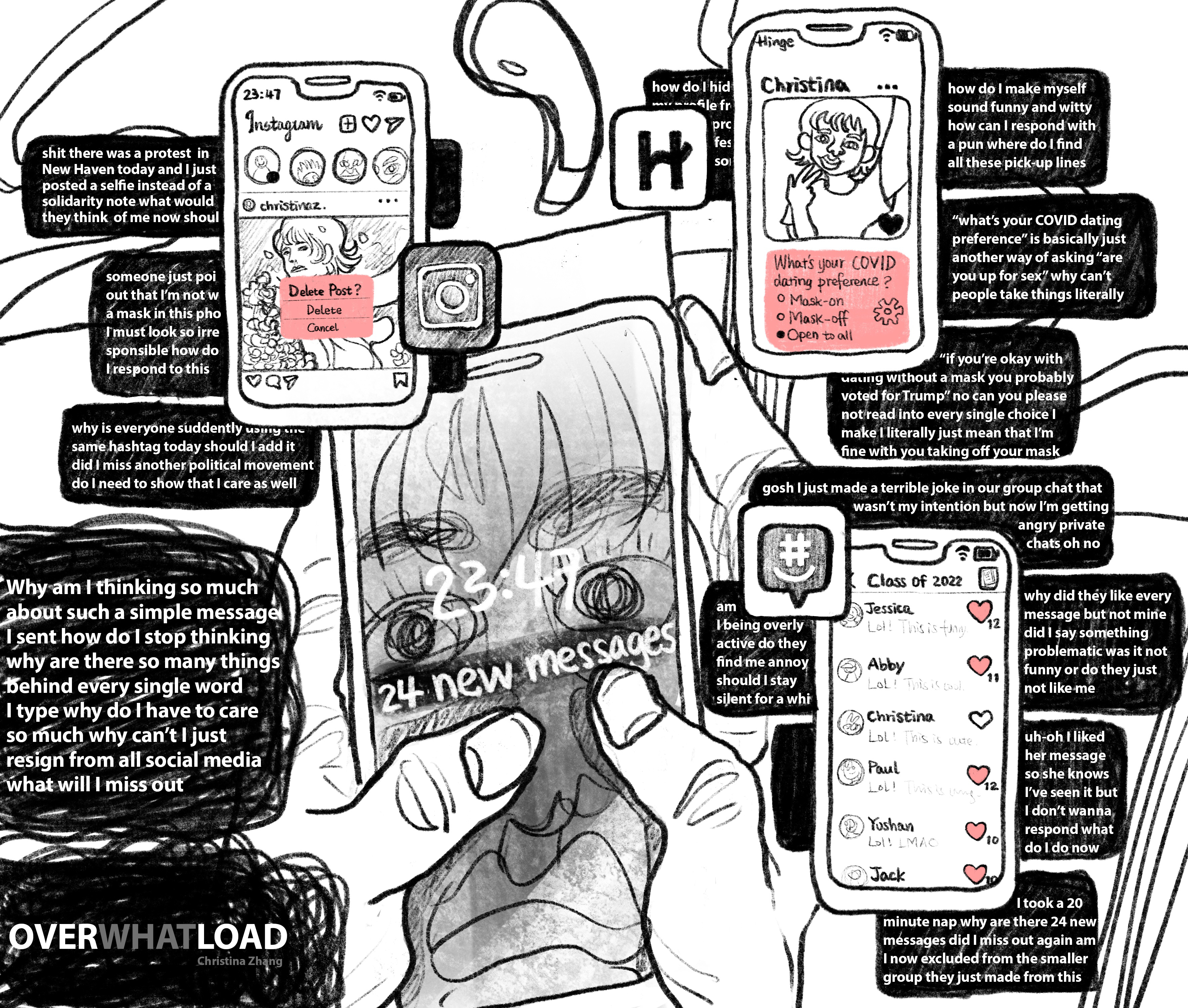

24 New Messages

Christina Zhang

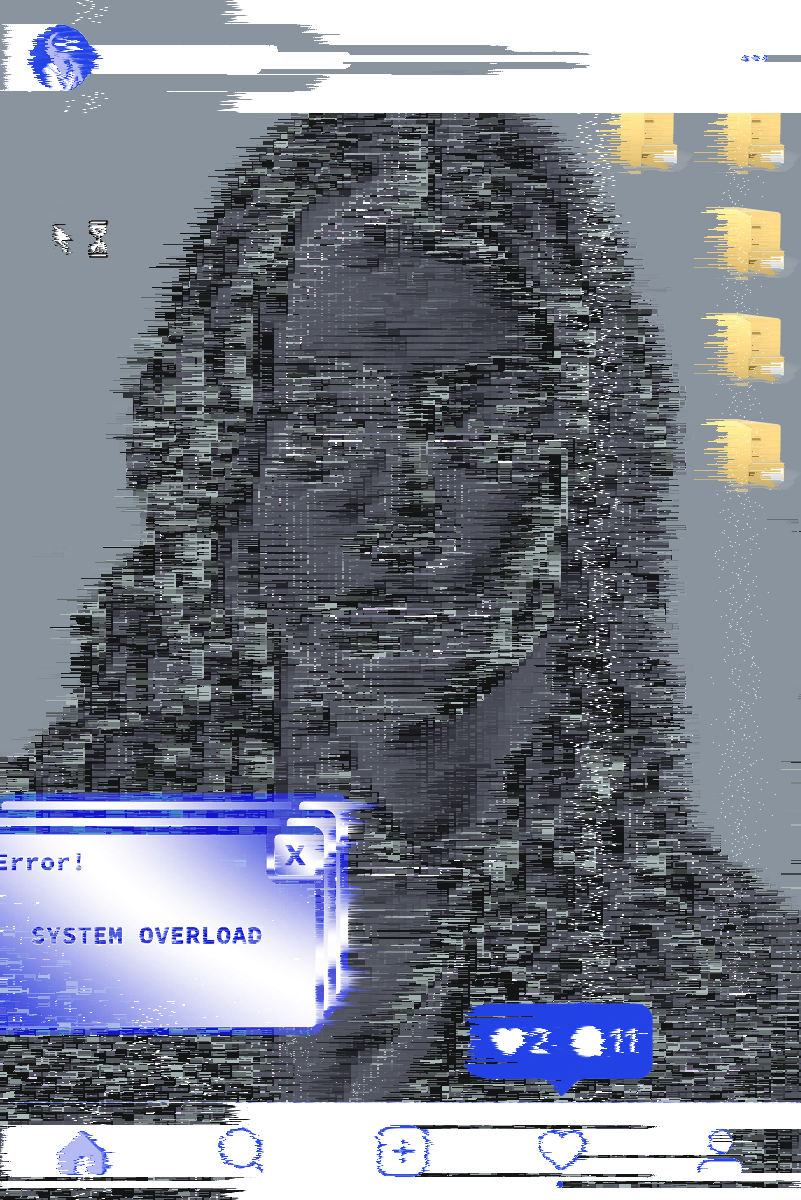

Human Error

Joshua Abramovich

The Glowing Rectangle

John Ceil